Tourist to Activist: My first visit to Palestine

Chelsea Milsom

I have recently graduated from Edinburgh University where I studied Arabic and am currently interning at Caabu. I first visited Palestine in the summer of 2011, when I travelled around with some friends and lived with a family in Dheisheh refugee camp. I subsequently spent my year abroad in Amman, Jordan and regularly returned to Palestine throughout the year.

The first time I visited Palestine there was no political motivation behind my trip, I was simply a tourist hoping to pass my three month summer holiday and improve my Arabic. By the end of the summer however, I was very much an activist for the Palestinian cause.

I reached East Jerusalem, my first destination in the Palestinian Occupied Territories via the King Hussein Bridge outside of Amman, Jordan. On the short bus ride across the Jordanian-Israeli border I was advised by some fellow backpackers not to mention to the Israeli border guards that I was intending to travel to the West Bank or else I would be denied entry. This alone baffled me, lying to officials contravened all of my instincts. On what grounds could Israel prevent people travelling to Palestine? Could Israel really attempt to deny the 4.4 million inhabitants of Palestine visitors?

My doubts over the validity of this claim were soon quashed: a couple in front of me at border control were swiftly denied entry when they admitted they were planning to visit the Occupied Territories. As they were taken towards the bus stop for those returning to Jordan I walked towards the desk, and after intense questioning about my previous trips to Arab countries I was eventually let through to visit the cities I had just denied planning to frequent.

Upon arrival in East Jerusalem I followed my guidebook’s advice and wondered through the majestic souq stalls, ate my first Palestinian falafel and hummus, bought a keffiyeh to keep my shoulders covered and chatted to Palestinians very eager to tell Western visitors about the detrimental effects of occupation on their quotidian lives. In the evening my group and I headed to the Western Wall: a contentious religious site claimed by Muslims and Jews that has been under Israeli control since 1967. At the end of the souq you had to go through security check flanked by teenage soldiers carrying guns. After an intense search, which included the confiscation of my newly purchased keffiyeh – a contemporary sign of Palestinian resistance, we were allowed to enter an area which is completely off limits to Palestinians. Unbeknown to us it was the Jewish festival of Shavuot and the Western Wall was filled with thousands of religious Israeli Jews singing and dancing seemingly oblivious to the checkpoint 200 metres away and the Old Testament commandment ‘Love thy neighbour.’

There is little typically 'Middle Eastern' about West Jerusalem, it is packed with fancy artisan coffee shops and restaurants, and could almost feel like a Western city were the streets not filled with off duty IDF soldiers who brandish their guns as female tourists walk by, keen to show off their military bravado. With ease my group refused their offers to go for a drink, and feeling rather unsettled surrounded by so many armed adolescents we asked a nearby man for directions to Damascus Gate in East Jerusalem. The man gave us a smirk and walked away whilst saying ‘I don’t know where you are talking about.’ None of us could quite believe it; the man had actually tried to pretend he didn’t even know the Palestinian area of the city existed. Feeling perturbed by the blatant apartheid in the supposed most religious city in the world we decided to leave Jerusalem to venture further into the West Bank.On the way to Nablus the overcrowded bus stopped at a checkpoint, three border control officers got on and ordered all those carrying Palestinian I.D cards to get off the bus and face a long queue and an unnecessarily long identity check before the bus could continue. I felt embarrassed as a quick flash of the exterior of my British passport meant I could stay on the bus. The Palestinian men, women and young children waited patiently as the border control sought to inconvenience them as much as possible, leaving for two cigarette breaks in the middle of the I.D card check. I felt overwhelmed with admiration for the Palestinians living under occupation. For them these checkpoints are an unavoidable, humiliating daily occurrence and for those who commute to other cities for work they add hours onto their journey time.

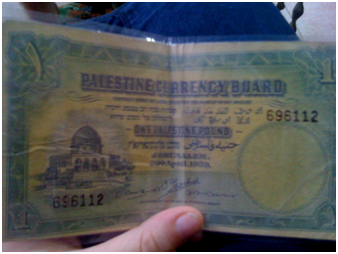

Nablus itself is beautiful, and despite being only 11 square miles it is home to over 100 mosques meaning the adhan, the call to prayer, can be heard from every corner of the city. The more laidback life without the presence of Israeli soldiers made me even more aware of Israeli occupation’s detrimental effect on Jerusalem, the holy city. But despite the absence of soldiers, the political situation is still painfully obvious. Political art covers the walls of the old city and everyone you meet is eager to have their story heard. I was overwhelmed by the friendliness of strangers: we sat in a coffee shop to have tea and shisha, and after a small chat with the owner he went down the road leaving us in charge. He returned with ‘the best food in Palestine’ for us to feast on, and wouldn’t let us leave until we had eaten it all! Another man we met insisted on giving us a tour of Nablus, which included visiting his favourites of the 100 mosques and drinking tea with several members of his family. After having been in his company for a few hours, he decided to show us his most prized possession: old Palestinian bank notes which he has had laminated and constantly keeps in the pocket of his thawb nearest his heart.

The people I met in Nablus were still full of hope that the separation barrier will fall and the occupation will end. In Hebron however those I met were more defeatist, rather than hoping to return they were hoping for exile into the neighbouring countries. It is easy to understand why, 700 Israeli settlers are concentrated in and around the old quarter, and the city is split into two sections, H1 which is controlled by the Palestinian Authority, and H2 which is controlled by Israel. Shuhada Street was once the heart of a bustling city centre but is now a desolate eerie street filled with abandoned shops and houses. Initially the street was closed off to vehicles in 1994 when an Israeli settler killed 29 Palestinian worshipers in a mosque, but following the second intifada in 2000 Israel increased its restrictions and shut the street off to Palestinians completely. Its closure has caused 77% of commercial Palestinian establishments to shut, and the Palestinian residents of Hebron have had to radically alter their lives to deal with the occupation of the city as well as the violent discrimination from armed settlers who continue to claim more houses in Hebron. One chronically ill woman who lives in sight of the local hospital now has to make a 6km journey around the settlements to reach the hospital that should be a five minute walk from her house.

There is no doubt that Hebron represents some of the worst manifestations of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories. The street which has replaced Shuhada Street as the commercial centre is patrolled by the army every Saturday so the settlers can walk through. Many Palestinian residents of Hebron told us stories of the settlers hurling abuse and spitting at them. Stories which are not hard to believe when one reads the graffiti in Shuhada Street, which tragically reads ‘gas the Arabs.’

The day I spent in Hebron was emotionally draining, so instead of staying overnight as planned I left for Bethlehem. I got on the bus filled with sympathy for the residents whose lives are marred by the occupation of Hebron, and are unable to just hop on a bus elsewhere. Unlike the romantic images I had of the birthplace of Jesus, Bethlehem was hardly a refuge from the devastating impact of the occupation. Again I had to pass through checkpoints, and was so shocked and saddened to see the 8m high separation wall encircling the holy city. A friend in the neighbouring town Beit Sahour with whom we were staying took us on a tour of the wall. Each time we saw the wall take an unusual turn in its path he pointed out the settlements, water reserves and olive plantations that it purposefully moved to encompass.

As well as travelling around Palestine, I also spent some time living with a family in Dheisheh refugee camp outside of Bethlehem. The family consisted of husband, wife and two children. The husband has a residency permit for Jerusalem, but his wife and children were denied residency permits so they live in Dheisheh. Defiant to withstand the occupation and Israel’s attempts to force more Palestinians out of East Jerusalem, the husband works two jobs to maintain two houses, one in East Jerusalem and the other in Dheisheh. To maintain his right to live in Jerusalem he is forced to live away from his family for at least half of the year, and regularly commutes from Bethlehem to Jerusalem – a journey that can take him several hours. He however says the inconvenience is all worth it when he can pray at the Dome of the Rock.

Sumud, steadfastness or determination is an Arabic word often used to describe the Palestinian people’s defiance in the face of a very unjust occupation. The father of the family with whom I stayed was an exemplary representation of that approach. It is his passion, as well as that of the others whom I met, that inspired me to do what I can for the Palestinian cause. Since my return from the Occupied Palestinian Territories I have joined the BDS movement (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) and attended protests in the hope that the apartheid policies practiced by Israel will be forced to end. I advise anyone who attempts to justify Israel’s violations of international law to go and visit Palestine, and see for themselves the inexcusable practices of Israel.