On the 21 June Caabu hosted a meeting on LGBTQ+ rights in Iraq with Amir Ashour, leader and founder of IraQueer, Iraq’s first and only organisation for the LGBTQ+ community in Iraq including the Kurdish region.

Ashour described not only the current situation in Iraq for members of the LGBTQ+ community, but also the ways in which both Britain and the global community could help affect positive change in the fight for human rights for this minority group. There is a particular dearth of discussion on LGBTQ+ issues in the Middle East, something Ashour actively seeks to combat.

One of the prevalent Iraqi misconceptions surrounding homosexuality is that it is a western import in Iraq and did not exist before the American invasion in 2003, creating both an anti-west as well as a homophobic element to many of the attacks in Iraq. Ashour emphasised the importance of telling the stories of LGBTQ people in Iraq, who are “as local as anyone else, not a western import.” ISIL’s actions for example, throwing gay men from tops of buildings in Iraq, created yet more reluctance around acknowledging sexual minorities. As well as these more recent complications, Amir spoke about the continued active denial by the Iraqi government of homosexuality. In a UN meeting, the delegation from Iraq claimed that homosexuality is against Islamic values. These documents are often not released to the Iraqi populace, meaning that this governmental trend is concealed from its own people. The Iraqi government, Ashour claims, has been actively attempting to criminalise homosexuality since August 2015.

Ashour stated his belief that, whilst many in Iraq do not have a particular opinion on the LGBTQ+ community, there is a culture of fear which prevents people from expressing any sort of positive or even neutral stance on issues of sexuality. This fear is undoubtedly fuelled by the number of attacks perpetrated against LGBTQ+ individuals, for which there are no definite statistics. However, there are clear examples of significant violence, as in July 2014 when 36 sex workers and LGBTQ+ individuals were killed on a single day by a Baghdad militia, Asa’ib Ahl alHaq, (the League of the Righteous). Many messages received by members of IraQueer are homophobic, and come from both strangers and close relatives. This highlights the bravery of those who do continue to post about their lives as queer Iraqis.

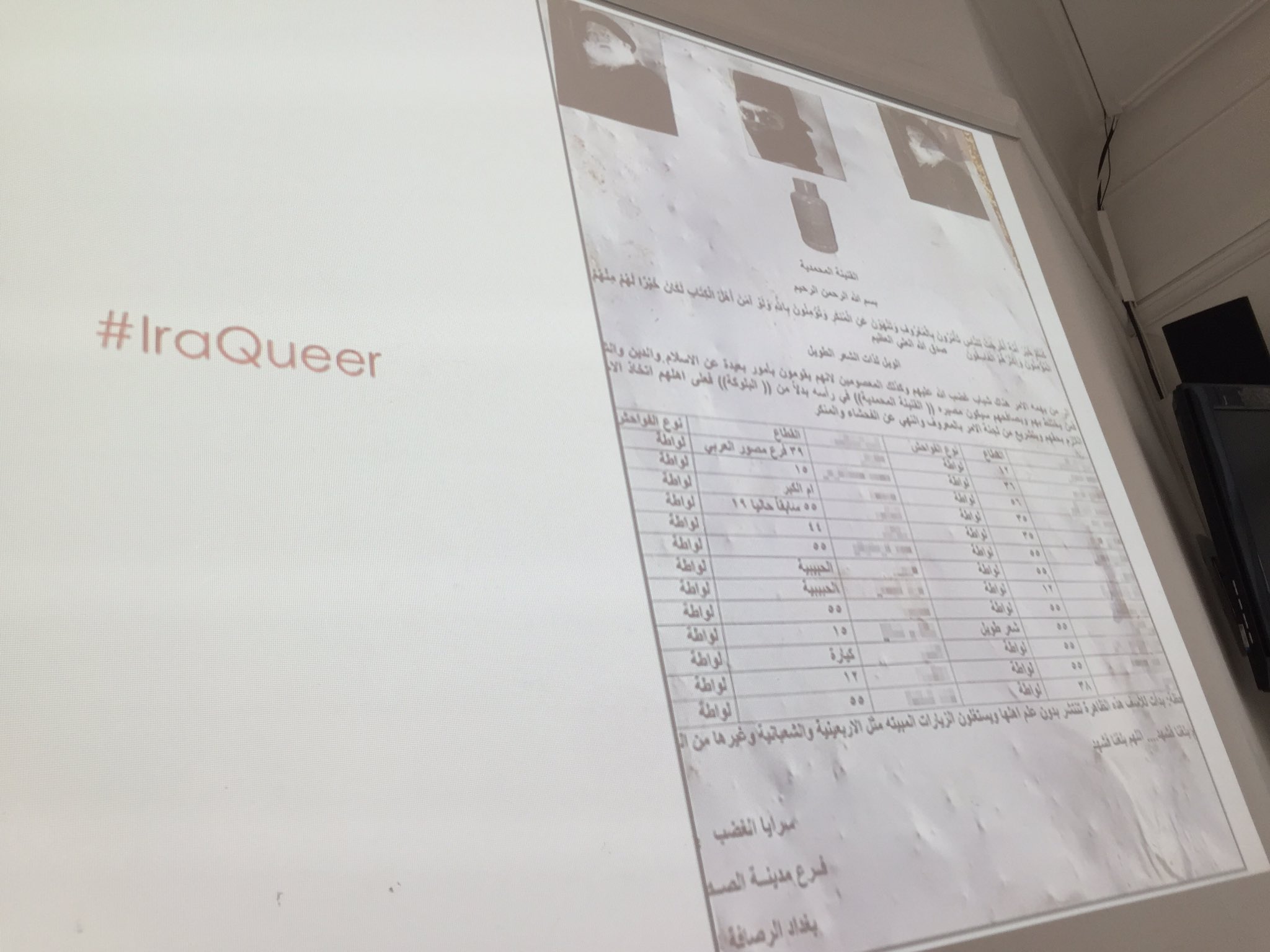

Life in Iraq has become particularly dangerous for LGBTQ+ individuals as even whilst the major power factions war over other issues, they tend to unite over the treatment of the queer community. Given the prolific release of fatwas by militias against LGBTQ+ Iraqis, including one released with the names of 23 “faggots” and one person with the crime of having long hair, individuals live in constant fear of discovery and consequently death. Fear of association with homosexuality is also rife, as even suspicions of “perverted” behaviour can result in a death sentence. Despite this, IraQueer has grown from one member (Amir) to 40 team members since its establishment, all unpaid. Given the dangers of being openly gay the group keeps the anonymity of all its members except Ashour (providing them with emoji avatars to post behind on the website).

Of the 16 core members that operate the site, 12 currently live inside Iraq, including Amir. Those outside are often engaged in helping members seek asylum. One of the issues that face those seeking asylum due to their sexuality is the dated nature of reports about Iraq LGBTq communities that most countries possess. Ashour pointed out that the report that Sweden currently uses is from 2013, which does not include therefore the impact that ISIL has had on the situation. He spoke heatedly of the invasive ‘proof of sexuality’ tests many are forced to go through when they are aksed to prove that they are gay. Typically they also have to endure homophobic and transphobic abuse in camps. This is also echoed in areas asylum seekers are settled into as their appeal is processed. Asylum seekers are expected to integrate, but not only are they denied access to language classes but quite often they are situated in areas which have pre-existing issues both with immigrants and LGBTQ+ communities.

Ashour said that “the more I was out, the less my living space was in Iraq.” All of the LGBTQ+ population in Iraq want to leave, he said; the only thing that stops them is that they lack the means. There is a choice between being killed and leaving Iraq, and for many, that is a choice they quite literally cannot afford to make. For those who cannot leave the country no haven can be offered; safe houses are illegal and classed as brothels in Iraq. Once individuals are in the process of seeking asylum they find they are lacking the documents officials expect them to have such as records of their imprisonment to prove their suffering for their “crimes” in Iraq, or even proof of their first boyfriend or first sexual experience.

The group is supported locally by some women’s groups but due to the negative association LGBTQ+ rights can bring in Iraq few are willing to be publicly affiliated. Queer women are often doubly as underground as the rest of the community, given their restrictions in public spaces. Many are also killed as ‘prostitutes’ instead of acknowledging their sexuality as the reason for death which continues the theme of erasure of queer women.

Ashour delineated four regions of Iraq and their individual difficulties for LGBTQ+ rights. He argued the ISIL controlled areas were probably the worst for denigrating the LGBTQ+ population and the least safe. The South, mainly run by tribal family hierarchies, is more conservative and homogenous than other regions, and whilst there is a suggestion that being gay in private is acceptable, the region’s opacity regarding the treatment of queer individuals makes it dangerous too. The central cities are more open, which means that militias are more likely to have access to potentially harmful information. The Kurdish region is highly regimented and, though nominally accepting, homophobic attacks are quite often simply classed under honour killings and hand-waved away.

Speaking about international support, Ashour stressed that this was a fight to be led by Iraqis, for Iraq. However, the group does need both funding and people willing to assist in raising visibility, and Ashour welcomed help with both these issues. He stated again that he was keen to work with other organisations sharing similar ideals. He also reiterated that IraQueer sees no reason why religion and orientation cannot be reconciled, and urged against the propagation of this false dichotomy.

The platform has a weekly reach of 8,500, with 11,000 regular readers, over half of whom are found in Iraq. Whilst there are bountiful pejorative messages, there is also an outpouring of positive feedback through the site, with messages coming through saying: ‘Thank you, we finally feel represented.’

The group has been mentioned in Jessica Stern’s concluding remarks, which reads:

“In conclusion, I want to share a ray of hope. Recently, a gay friend from Iraq founded a new organization for LGBTI Iraqis: IraQueer. Now with members across the country, they’re finding ways to survive -- even in ISIS-controlled areas.

If they can find a way, so can the international community. Today is a first step.”

More information on IraQueer can be found here